The Eternal Paternal

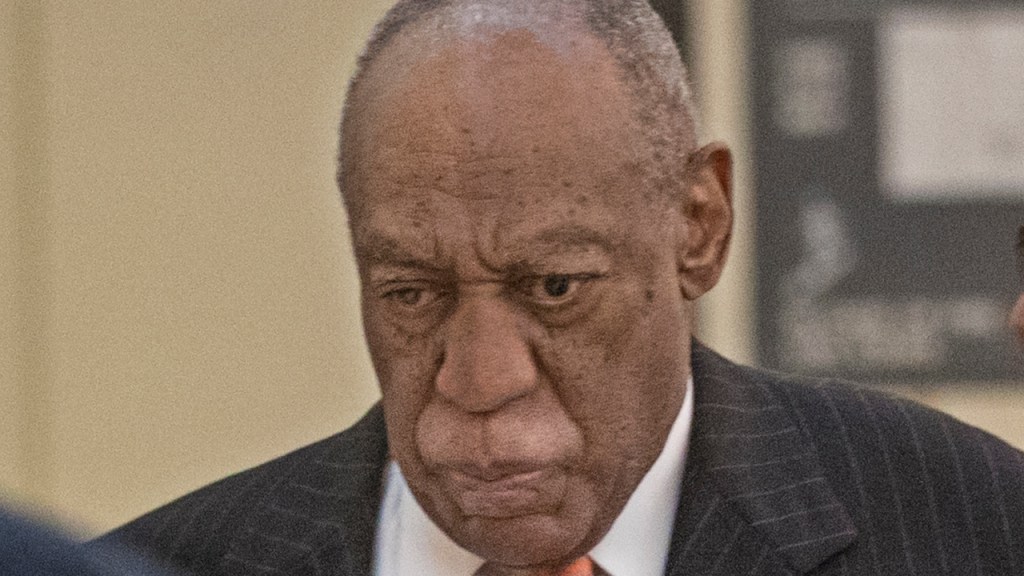

Awarm summer weekend was just beginning in Salisbury, Maryland, and cars were pulling into the parking lots that surround the Wicomico Civic Center. People had come to see Bill Cosby, who would remind them, that night, that he was “seventy-six and eleven-twelfths years old,” and who surely has neither the time nor the need to do anything he doesn’t want to do. What he does want to do, even now, is comedy: he performs about a hundred times a year, mainly on weekends, following an itinerary that often leads him into what promoters call tertiary markets, where fans are not just happy to be able to see him in person but surprised, too.

The Civic Center arena had been converted for the night into a theatre with about two thousand seats, most of which were full by the time Cosby shuffled onstage, a few minutes past eight. When he began his career, more than fifty years ago, Cosby wore natty suits and narrow ties, but these days his performance attire tends to be casual, often flamboyantly so: T-shirts, sweatpants, sandals, socks. He had been provided a chair and a small side table, and as he settled in he rubbed his knees and looked around. “Well, here I am,” he said. He asked what else the arena was used for. “Rodeo!” someone shouted. “The circus,” someone else said. Cosby brightened. “I remember hearing about the circus as a child,” he said, and then stopped short. When other comics talk about Cosby, they often mention his willingness to pause without filling the silence, certain that the audience trusts him enough to keep listening. When he began again, he was talking about being too poor to go to the circus, which set him off on a twenty-five-minute riff about childhood and poverty and an armchair so rickety that his father had to sit perfectly askew so that it didn’t fall apart.

Cosby has always been an economical but effective physical comedian; people howled as he shifted cautiously in his seat, imitating his father in that chair. But his greatest weapon is his strained and stentorian voice, which is easy to imitate but hard to parody, because Cosby’s bewildered vehemence can scarcely be exaggerated. Often, his jokes come alive only in performance, fuelled more by the telling than by the words. In Salisbury, he reminisced about his wife, Camille, who was nineteen when he married her, in 1964. “She was not who she is today,” he announced, and the audience was laughing already. “She was a nice person.” More laughter, and then applause. “You know what I’m saying. If you are married, then you know the way you look at him.” He imitated a wife’s disapproving appraisal, his face serving as the punch line.

In Cosby’s comedy, he returns endlessly, even obsessively, to this basic plot: the struggle of a man against the woman he has chosen and the children he hasn’t. When “The Cosby Show” made its début, in 1984, he was already one of the most successful comics of his generation, and a television star of long standing. The show made him an American archetype: the personification of fatherhood, a word that was also the title of his best-selling book of observations and advice. When he takes the stage, he remains more than anything an exasperated father. Confronting the cosmic impertinence of a child who moans, “I didn’t ask to be born,” Cosby responds, as always, with fond irritation. “Yes, you did,” he says. “About nine months before you were born, I released about sixty million—you were one of ’em. The idea is, first one to the egg locks the door. The others die.” He pauses to let the laughter subside, then turns accusatory: “You could have hung a left.”

Cosby’s current tour is part of a long comeback. His most recent comedy special, “Bill Cosby: Far from Finished,” was broadcast on Comedy Central last year, and he is at work on a new NBC sitcom, tentatively scheduled for 2015, which would reunite him with Tom Werner, one of the executive producers behind “The Cosby Show.” At the same time, he is living through an extended retrospective celebration. In 2009, he collected the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor, and earlier this year Chris Rock presented him with a lifetime-achievement honor at the American Comedy Awards, calling him “the greatest comedian to ever live.” Now comes “Cosby: His Life and Times” (Simon & Schuster), a biography by Mark Whitaker, the former editor of Newsweek; the book, written with Cosby’s participation, is invaluable but not, of course, impartial. Unlike most of the lions of American comedy, Cosby is known for routines that aim to avoid giving offense, and yet he has proved surprisingly controversial: for decades, he was regularly criticized for being insufficiently attentive to issues affecting black communities; more recently, he has been passionately attentive, transforming into a culture warrior to deliver fierce indictments of what he diagnoses as an African-American social pathology.